Translating on Behalf of Animals: Lessons from Ursula K. Le Guin

Originally published: December 1, 2022 on pH-auna.com, revisited August 15, 2025Understanding Animals, With Humility and Imagination

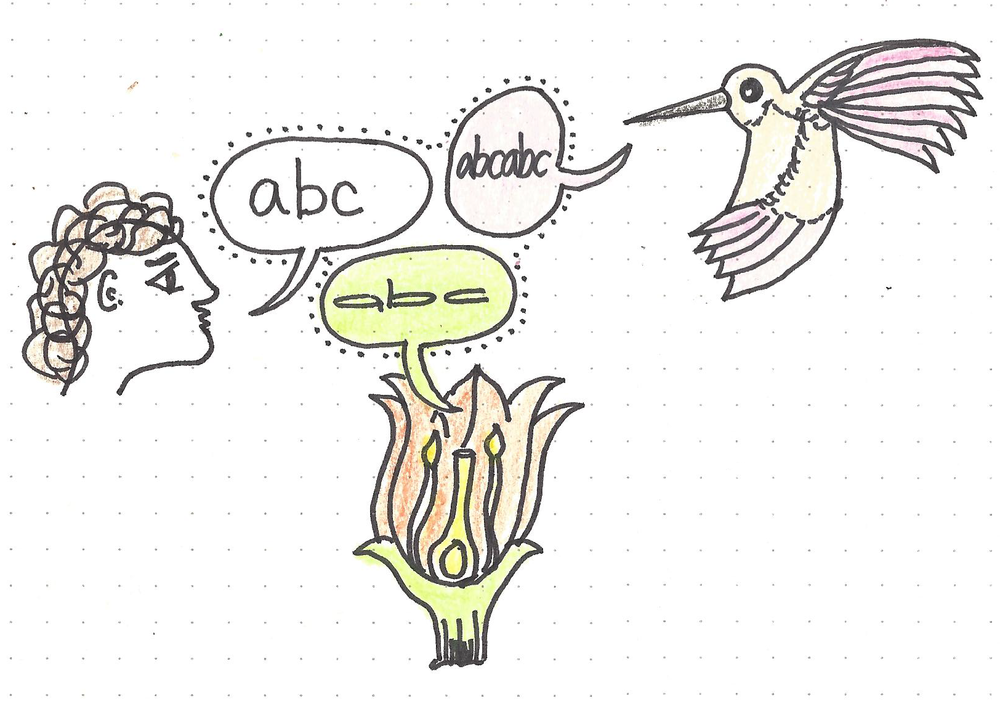

Designing for and with animals inevitably places us in the uncomfortable—and deeply human—role of translator. We are tasked with interpreting the behaviors, signals, and needs of beings whose experience of the world differs fundamentally from our own. Our challenge is not just technical or observational, but also ethical and imaginative.

In animal centered design, we walk a fine line: using our cognitive abilities to empathize, while resisting the temptation to overly humanize. Translation is necessary—but always partial. The question is not only how we translate, but from what, into what, and within what context.

Le Guin and the Ethics of Translation

This tension is at the heart of one of my favorite short stories:

“The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics” by Ursula K. Le Guin.

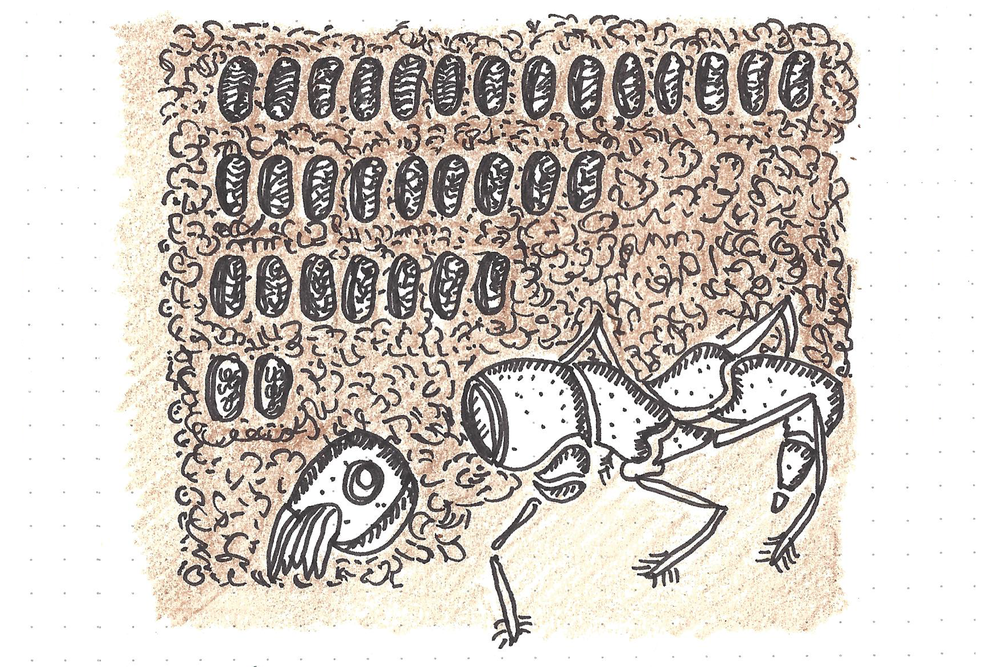

In this fictional academic report, Le Guin invents the field of therolinguistics—the study of beast language—and weaves together a series of speculative translations, beginning with a message allegedly left by an ant before her colony’s downfall.

“Degerminated acacia seeds laid in rows”

—a war-time message, written by a wingless neutered worker (as soldier ants, Le Guin reminds us, are illiterate).The phrase: “Up with the Queen.”

At first, human interpreters read this as a loyalist rally cry. But from within the social norms of an ant colony, up may mean exile—lifting the Queen out to her death. Suddenly, the phrase reveals itself as potential rebellion.

A simple word, up, unravels our assumptions. It’s a brilliant reminder of how translation across species requires more than linguistic cleverness—it requires epistemic humility. What seems obvious from one lens may carry radically different meaning from another.

Beyond Analogy: What Le Guin Offers to Animal Centered Design

The story continues with a fictional expedition to decode “penguin sea writings”—a kinetic language written in wings, neck, and air. And later, an editorial on the absurdity of trying to “read Eggplant,” only to reveal the hubris of our disbelief in non-human communication.

Three powerful insights for animal centered design emerge:

Species are socially and cognitively distinct.

Just like humans, individual animal species have varied and culturally embedded communication styles that defy simple analogies.Translation is shaped by power and perspective.

Our tendency to favor what resembles us (like Emperor penguins over Adelie) may limit what we’re willing—or able—to hear.We must hold space for the unknown.

As Le Guin’s fictional phytolinguist reflects: just because we can’t yet hear it, doesn’t mean it isn’t being said.

Designing With This in Mind

For those of us working in animal anything, Le Guin offers more than metaphor. She proposes a radical shift in posture - from certainty to curiosity, from dominance to listening.

The world, and all the beings within it, are more complex than we know. And our job as designers, biologists, technologists, ethologists … you name it is not to simplify that complexity, but to remain open to it.

Nature speaks.

We’re still learning the language.