Blog

The Expansive Potential of Animal Centered Design

For most of design history, the word user has referred exclusively to humans. But as our world becomes more interconnected—and increasingly shaped by ecological crisis—it’s time to rethink that assumption.

Animals are part of our ecosystems, cities, homes, and inner lives. Including them as legitimate users in the design process isn’t just an ethical move—it’s a practical, creative, and even transformative one.

Animal centered design (ACD) opens up a powerful range of possibilities that extend far beyond pet products or wildlife tech. Here are three of the most promising applications.

Originally published: January 18, 2023 on pH-auna.com, revisited August 15, 2025For most of design history, the word user has referred exclusively to humans. But as our world becomes more interconnected—and increasingly shaped by ecological crisis—it’s time to rethink that assumption.

Animals are part of our ecosystems, cities, homes, and inner lives. Including them as legitimate users in the design process isn’t just an ethical move—it’s a practical, creative, and even transformative one.

Animal-centered design (ACD) opens up a powerful range of possibilities that extend far beyond pet products or wildlife tech. Here are three of the most promising applications.

1. ACD as a Design Discipline

At its most straightforward, ACD is a method for designing products and services that meet both animal and human needs.

This includes:

Veterinary clinics

Companion animal products

Farm infrastructure

Enclosures, shelters, and wildlife interventions

By observing species-specific behaviors, applying ethical reflection, and designing with empathy, we can create environments and systems that support well-being across species.

2. ACD as a Strategy for Understanding & Belonging

This might be surprising, but animal centered design can serve as a tool for teaching empathy and non-judgmental observation, especially effective because, with animals, we naturally begin without bias. Using ACD methods helps people learn how to set assumptions aside and attend deeply to others' needs. These skills then seamlessly translate to any context where understanding and belonging is key - which in all honesty are most human contexts.

Here’s why:

We relate to animals without judgment.

From early childhood stories to animal characters in media, we learn empathy before bias. We often suspend judgment when trying to understand an animal’s behavior.Nobody is an expert in all animals.

This levels the playing field—everyone is curious, everyone has something to learn.

At pH‑auna, we’ve used ACD methods to help people examine their own assumptions in non-threatening ways. Exercises that begin with observing and interpreting animals to build skills that transfer directly to more complex, human-focused work.

3. ACD as a Bridge Between Urban Humans and Nature

This third point is speculative—but deeply intuitive.

Since the 1970s, we’ve seen three parallel trends:

Urbanization has physically and psychologically disconnected people from nature.

Scientific understanding of climate change has grown.

Pet ownership has surged—over 1 billion companion animals live with us globally.

What if pets aren't just companions?

What if they are living intermediaries quietly reconnecting us to the natural world?

Most urban dwellers won’t see a whale, tomato plant, or cow in their lifetime. But they will see a dog curled on the couch, or a cat chasing dust motes in the light.

When I ask you what your pet loves, you think of them as an individual. A one-of-a-kind being. If I then ask you to imagine a polar bear or whale the same way, the leap doesn’t feel as far.

Perhaps animal-centered design is not just about designing for animals—but designing with them to heal our relationship to nature.

In Closing

Animal centered design is more than a method. It’s a mindset. A quiet invitation to expand who we consider worthy of design, care, and attention.

The ripple effects, from product design to social belonging to ecological awareness are profound.

And we’re only just beginning.

Translating on Behalf of Animals: Lessons from Ursula K. Le Guin

Originally published: December 1, 2022 on pH-auna.com, revisited August 15, 2025Understanding Animals, With Humility and Imagination

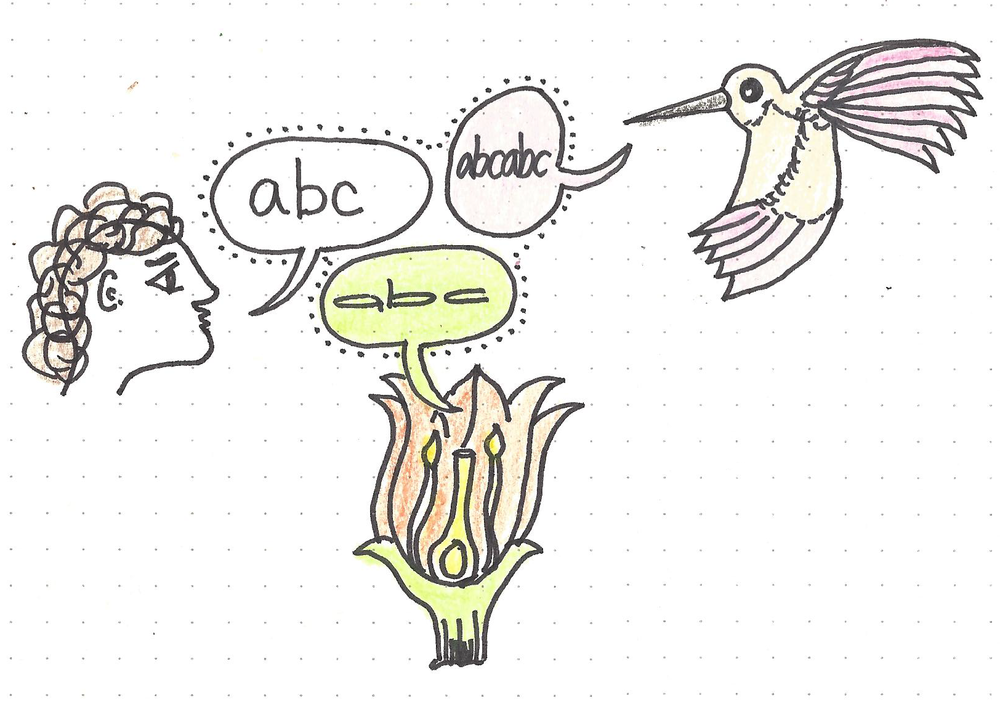

Designing for and with animals inevitably places us in the uncomfortable—and deeply human—role of translator. We are tasked with interpreting the behaviors, signals, and needs of beings whose experience of the world differs fundamentally from our own. Our challenge is not just technical or observational, but also ethical and imaginative.

In animal centered design, we walk a fine line: using our cognitive abilities to empathize, while resisting the temptation to overly humanize. Translation is necessary—but always partial. The question is not only how we translate, but from what, into what, and within what context.

Le Guin and the Ethics of Translation

This tension is at the heart of one of my favorite short stories:

“The Author of the Acacia Seeds and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Therolinguistics” by Ursula K. Le Guin.

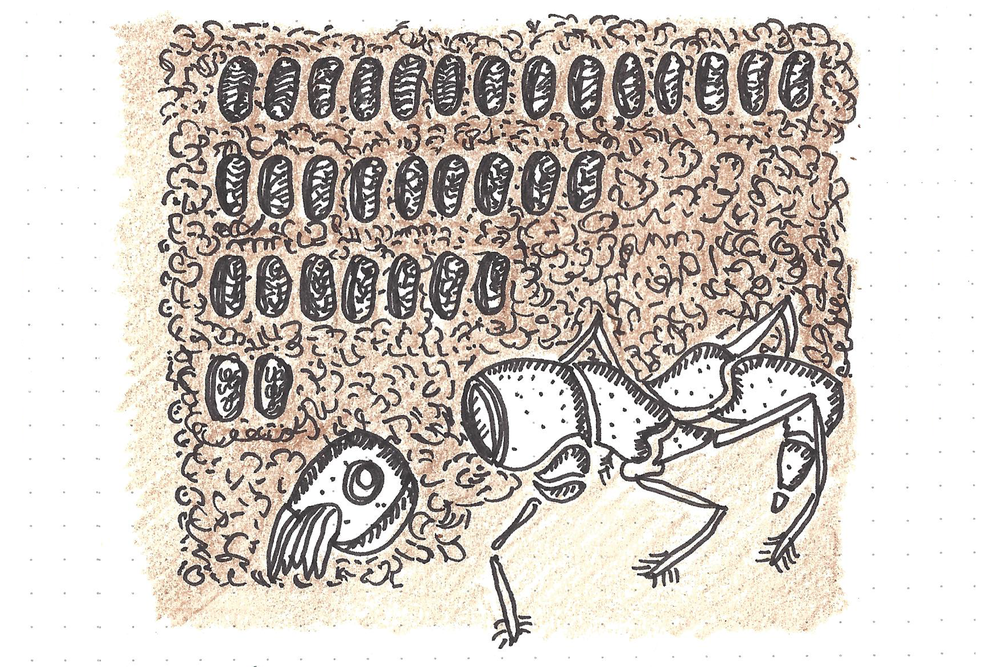

In this fictional academic report, Le Guin invents the field of therolinguistics—the study of beast language—and weaves together a series of speculative translations, beginning with a message allegedly left by an ant before her colony’s downfall.

“Degerminated acacia seeds laid in rows”

—a war-time message, written by a wingless neutered worker (as soldier ants, Le Guin reminds us, are illiterate).The phrase: “Up with the Queen.”

At first, human interpreters read this as a loyalist rally cry. But from within the social norms of an ant colony, up may mean exile—lifting the Queen out to her death. Suddenly, the phrase reveals itself as potential rebellion.

A simple word, up, unravels our assumptions. It’s a brilliant reminder of how translation across species requires more than linguistic cleverness—it requires epistemic humility. What seems obvious from one lens may carry radically different meaning from another.

Beyond Analogy: What Le Guin Offers to Animal Centered Design

The story continues with a fictional expedition to decode “penguin sea writings”—a kinetic language written in wings, neck, and air. And later, an editorial on the absurdity of trying to “read Eggplant,” only to reveal the hubris of our disbelief in non-human communication.

Three powerful insights for animal centered design emerge:

Species are socially and cognitively distinct.

Just like humans, individual animal species have varied and culturally embedded communication styles that defy simple analogies.Translation is shaped by power and perspective.

Our tendency to favor what resembles us (like Emperor penguins over Adelie) may limit what we’re willing—or able—to hear.We must hold space for the unknown.

As Le Guin’s fictional phytolinguist reflects: just because we can’t yet hear it, doesn’t mean it isn’t being said.

Designing With This in Mind

For those of us working in animal anything, Le Guin offers more than metaphor. She proposes a radical shift in posture - from certainty to curiosity, from dominance to listening.

The world, and all the beings within it, are more complex than we know. And our job as designers, biologists, technologists, ethologists … you name it is not to simplify that complexity, but to remain open to it.

Nature speaks.

We’re still learning the language.

Designing Ethically with Animals: The Case for an Animal Centered Toolkit

Originally published: November 1, 2022 on pH-auna.com, revisited August 14, 2025The Challenge of Designing for Animals

Designing with empathy is at the core of good design—but what happens when your intended user can’t speak for themselves, and are of a different species? Compared to working with humans (even those that might be non-verbal) animal centered design (ACD) introduces a deeper level of complexity. Designers must rely on observation, interpretation, and ethical imagination to understand animals’ experiences and needs.

As an animal centered designer, you’re tasked not only with crafting usable systems, but with making ethical decisions on behalf of a user whose feedback is non-verbal and whose perspective you can never fully inhabit. This calls for rigorous ethical reflection, grounded observation, and critical inquiry throughout the design process.

From Principles to Practice: A Gap in Ethical Tools

During my doctoral research into service dogs' interactions with buttons, switches, and access controls, I encountered several well-structured ethical frameworks. Most, however, were normative: offering high-level principles but limited support for real-time, context-specific decision-making.

In the field, I was constantly making moment-by-moment decisions influenced by my own ethical stance. The need became clear: a practical, adaptable tool to support designers in navigating ethical uncertainty in real-world ACD projects.

Introducing: The Ethics Toolkit for Animal-Centered Design

This need led to the creation of the Ethics Toolkit for Animal-Centered Design - a set of three templates designed to help designers reflect, plan, and adapt ethically across species-inclusive projects.

Here’s how it works:

Template 1: Designer’s Ethical Baseline

Encourages self-reflection on your understanding of the animal as a user and how that understanding shapes your role.Template 2: Project Ethical Baseline

Frames key aspects of the project: goals, intent, animal participation, harm minimization, and accountability.Template 3: Ethical Scenarios

Prompts designers to imagine and prepare for ethically charged situations and articulate project-specific ethical guidance.

Use and Share

The toolkit is published in the May 2022 issue of Frontiers in Veterinary Science.

🔗 Download the full paper here

I see this as a living resource. If you use or adapt the toolkit, I’d love to hear how. Your feedback can shape its next evolution. Feel free to share your experiences here.

Triangulation: The Backbone of Animal Centered Design

Originally published: January 8, 2023 on pH-auna.com, revisited August 14, 2025Make it stand out

Why Designing Across Species Requires Multiple Lenses

Designing for humans is already nuanced—but when we extend that practice to animals, we enter a world where our usual assumptions about feedback, communication, and usability fall short. Animals can’t fill out surveys or give us verbal insights. Their behaviors, while rich with meaning, often require interpretation.

So how do we responsibly and ethically design for beings we can’t directly interview?

The answer lies in a fundamental concept of robust design research: triangulation.

What Is Triangulation?

In the context of animal centered design, triangulation means using multiple sources, methods, and perspectives to understand the needs and experiences of animal users.

Instead of relying on a single approach like observation, expert input, or behavioral studies, we combine them. This creates a more layered, accurate, and ethically sound understanding of how an animal interacts with its environment, tools, and human counterparts.

Why Designing Across Species Requires Multiple Lenses

Designing for humans is already nuanced—but when we extend that practice to animals, we enter a world where our usual assumptions about feedback, communication, and usability fall short. Animals can’t fill out surveys or give us verbal insights. Their behaviors, while rich with meaning, often require interpretation.

So how do we responsibly and ethically design for beings we can’t directly interview?

The answer lies in a fundamental concept of robust design research: triangulation.

What Is Triangulation?

In the context of animal centered design, triangulation means using multiple sources, methods, and perspectives to understand the needs and experiences of animal users.

Instead of relying on a single approach like observation, expert input, or behavioral studies, we combine them. This creates a more layered, accurate, and ethically sound understanding of how an animal interacts with its environment, tools, and human counterparts.

Why Interspecies Design Is So Complex

Unlike human centered design, where designers often work within a shared cultural and cognitive framework, interspecies design has no such shortcut. The complexity arises from:

Species-specific perception (e.g., what a dog smells vs. what a human sees, or even what a dog smells vs. what a human smells!)

Non-verbal communication

Contextual behavioral patterns

Ethical considerations that must be adapted per species and context

No single method, be it observation, ethnography, or biometric tracking, can fully account for these variables. That’s why triangulation becomes essential: it allows us to cross-check insights, reduce bias, and deepen our understanding through contrast.

Triangulation in Practice

In real-world projects, this might look like:

Combining video analysis, caregiver interviews, and behavioral data to evaluate how a therapy dog interacts with a hospital environment.

Using ethological principles, sensor data, and contextual observations to inform the design of animal enrichment tools.

Layering design reflection, expert consultation, and animal welfare standards into each phase of a project.

Each layer adds dimension and helps mitigate the risk of misunderstanding or misrepresenting the animal user's needs.

Building Better Design Through Triangulation

Triangulation isn’t just about academic rigor. It’s a practical, compassionate tool for creating designs that truly serve animal well-being. It acknowledges the limits of our human perspective and offers a way to reach toward a more inclusive and species-aware design process.

In this way, triangulation becomes the backbone of ethical, effective, and creative animal centered design.